Free Alongside Ship

The Italian International Chamber of Commerce uses the following definition to describe this term:

FAS – Free Alongside Ship means that the seller delivers the goods by placing these alongside the ship (e.g. on a quay or a barge) as designated by the buyer at the named port of loading. The risk of loss or damage to the goods passes from seller to buyer when the goods are alongside the ship and it is the buyer bears all costs from that moment onwards.

In order to understand the principle aspects of the FAS term, it is important to bear in mind the individual segments that together as a whole make up the transport via ship. FAS is in fact a delivery term dedicated exclusively to maritime or inland waterways transport.

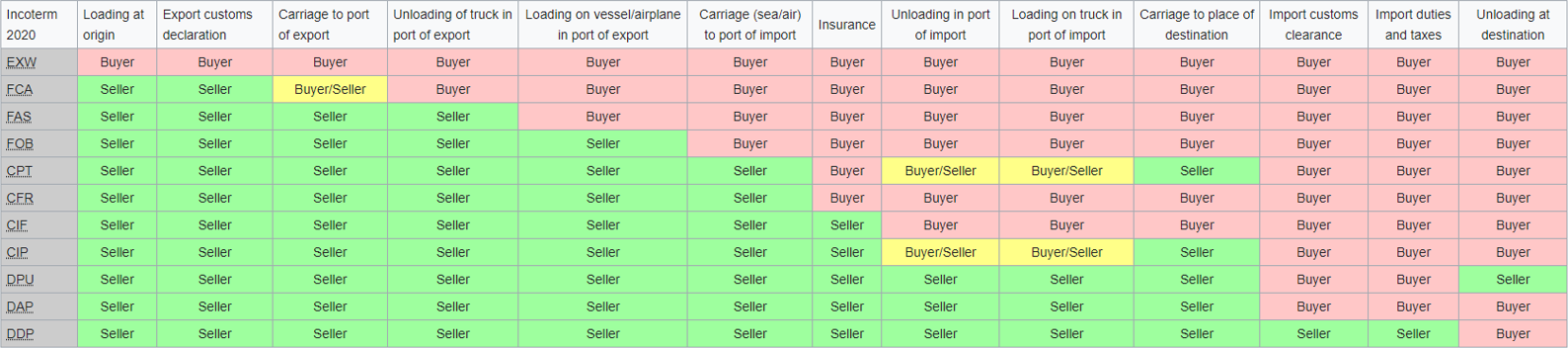

If we look at a door to door transport, i.e. from the manufacturer’s factory to the final consignee, we can break this down into 10 segments to which we add an additional segment relating to insurance cover for a total of 11 segments.

The segment that sets apart the FAS term from its closely related Group F terms (FCA and FOB) is the fact that the seller pays for the portion referring to the transport of goods to the dock.

So this is a step forward when compared to the FCA term, as we are no longer at the customer’s or shipper’s warehouse, but a step back when compared to the FOB term, because the goods are not loaded onto the ship, but are ready for shipment, where the costs and responsibilities are borne by the buyer.

Let us take a more detailed look at the goods and types of shipments for which FAS is almost exclusively used to help us understand the logic behind it: these are bulk or break bulk shipments, or the so-called Project and Ro-Ro cargo shipments.

Project Cargo: These are shipments of particularly large loads in terms of size and weight. A practical example: the transport of entire industrial plants that are moved to a geographical area or country where production is more efficient. In addition, shipments of production plants, propellers, pipes or mechanical components, tens of meters in length and weighing hundreds and thousands of kilograms. These are shipments commonly referred to as exceptional, heavy lift and oversized. Logically, these types of goods are unsuitable for loading into a container, but on the contrary, loading them on board, both in terms of physically placing them on the ship and in terms of ensuring they are correctly immobilized, requires drawing up a meticulous logistics project based on both in-depth technical expertise and engineering knowledge. Project Cargo is handled by on-board cranes (otherwise known as deck cranes).

Break Bulk: Here we are in the area of bulk transport, for example cereals, coal, iron, i.e. goods loaded on board ships and transported without being put into containers, but loaded into sacks, boxes, crates, drums or barrels or as cargo units on pallets or skids. Loading/unloading operations take place quickly via the use of hoppers and pneumatic systems, i.e. mainly with the use of port machinery. This was certainly a service used more frequently in the past; prior to the introduction of the container in the 1960s. At the time, it was the only way in which goods were forwarded on ships. Today, on the contrary, it has become a secondary, downsized maritime transport option. In fact, even if specialized bulk carriers are equipped with specific cranes capable of handling this type of cargo safely and more efficiently than port cranes, it is also true that when compared to container loading, the procedures require a much longer handling time and there is also a much higher rate of damage and theft.

Ro-Ro (the abbreviation for Roll-on/Roll-off shipments): This is the shipping of a moving or self-propelled means of transport. The object being transported is therefore a wheeled vehicle that is loaded and unloaded using its own wheels, or a load, arranged on a flatbed or in a container, loaded and unloaded autonomously by means of vehicles equipped with wheels, without the aid of further mechanical means (cranes, etc).

The Ro-Ro is therefore the preferred option for the automotive sector, especially for mass production shipments. The Ro-Ro shipments are also used when loading static cargo with the help of flatbed trailers, forklifts (so-called dry loading), or trucks (so-called garage loading) in the case of very light or very heavy goods. Once loaded onto the flatbed trailers these are hooked to either a truck, or depending on the size of the shipment, to a tug boat and either driven or towed into the belly of the ship via the cargo ramp.

The first characteristic common to the types of shipments as above, is that these types of shipments are very delicate and run a greater risk of accident during the process of actually loading the goods on board. Comparing this to the transport of cargo in containers, it is clear that both the integrity of the goods, as well as the safety of people and the environment, are more exposed during operations.

Secondly, maritime freight tariffs, i.e. the cost of the space occupied on the ship, are always agreed on the basis of the characteristics of the specific cargo, and it would therefore seem logical that the related loading costs should be charged to the same party that pays the maritime freight tariff.

To summarize, one can see how in the case of a sale under FAS terms, the seller tends to divest themselves of the risks that are inherent to the shipment of the goods they have sold. We have looked at the suitability of this type of choice. In broader terms, when referring to the Incoterms EXW, we could extend the same reasoning to all the terms in Group F and conclude that how much the shipper wants to be involved in the carriage of the goods sold depends on the individual company strategy to be applied – whether to use a more cost efficient option or to creating what can be considered as an intrinsic added value.

Autor: Francesca Savia

Operations and Compliance Manager

Savitransport – HQ Florence